Some years ago, a language-teaching colleague outside MY asked me, “Why are you teaching eikaiwa?”

For those unfamiliar with English language teaching in Japan, “eikaiwa” is often used as a catch-all term for private language schools and lessons. The word (英会話) combines the Japanese kanji characters for “English” and “conversation.” Eikaiwa (conversing in English) as an activity is often viewed positively among Japanese people. However, eikaiwa teaching is often viewed negatively among teachers and among foreigners in Japan.

While the aforementioned colleague has always shown high respect for MY English School, her general disdain for “eikaiwa” was evident in her question. I have a Ph.D. I am qualified to teach at the university level. Why would I choose to work at what she regards as the bottom of the teaching pecking order?

My answer left this colleague slightly flustered: “I don’t teach at an eikaiwa.”

This was not the answer the colleague expected. It required some explanation for her to understand why I rejected the label.

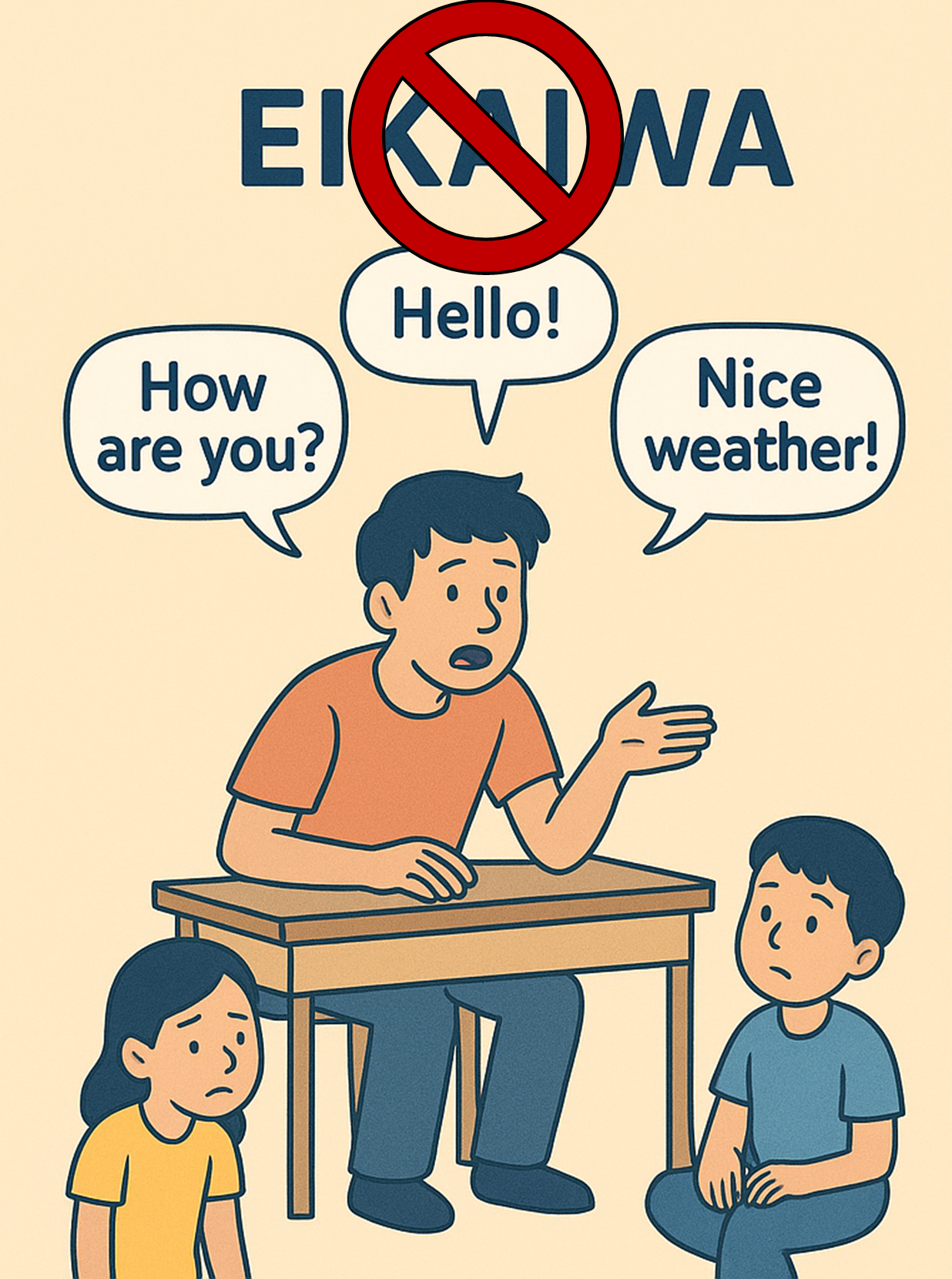

I dislike the term “eikaiwa,” both because of its educational history and its inaccuracy in describing most teaching today. There are situations and schools to which “eikaiwa” may still apply, but it’s a terrible description of the teaching I do.

Eikaiwa’s history

“Eikaiwa” is rooted in the history of public English education in Japan. Following the Meiji Restoration, lessons in all subjects were often taught in English at various schools and universities. English education was predominantly taught by foreigners, with a heavy emphasis on communication. As the primary educational language shifted to Japanese, English reading still mattered, while oral communication received less attention.

Early in the 20th century, English was made into an admissions requirement for higher education. English stopped being primarily a communication tool and shifted into and admissions tool. To some extent, this still describes the state of English education in Japan today: English is an important metric for school admissions. Entrance exam results remain more important than producing students who can communicate.

Following World War II, Japan expanded English education to the junior high school level. The sudden demand for English teachers far outstripped the supply of competent English speakers (let alone teachers) in Japan. Japan adopted a grammar-translation (yakudoku) method of teaching English, which hearkened back to 19th-century education in Europe, when the important languages at elite schools were Classical Greek and Latin. By the 1950s, this grammar-translation method was highly outmoded for teaching all modern languages. However, as Diane Nagatomo explains, it offered Japan a straightforward formula that could be evaluated in “right” and “wrong” answers and taught by teachers with relatively little expertise in English. Thus, Japan’s public schools taught English via memorization of grammar rules and vocabulary, applied primarily to English-to-Japanese translation.

For decades, to translate written English into Japanese via formulaic rules was sufficient for entrance exams. Public schools required little in terms of writing, conversing, communicating, or thinking in English. A few elite students found moderate success in English, but most students struggled with the arcane approach to language.

In response to this deficiency, “conversation schools” popped up across Japan. Some catered to adults who needed to communicate in English, but whose hours in junior high school, high school, and university had been wasted on mostly unproductive exercises that gave them few practical language skills. Many eikaiwa schools served as fun clubs for cosmopolitan-minded people who enjoy the idea of speaking English. “English conversation schools” focused on speaking English instead of on the grammar-translation that dominated in school.

The other big eikaiwa market was kids, much with the same rationale. Kids would learn grammar and translation in school, and so they needed separate “eikaiwa” practice. English in junior high school and high school was hard, and so eikaiwa lessons gave children a chance to have fun with English and get ahead before the serious English of public school started.

At many of these eikaiwa schools, the qualifications of the teacher did not especially matter. As long as the person spoke English, that was enough. This attitude of “any native speaker will do” carried over into the formation of the JET Programme and ALT system in public schools.

The rise of eikaiwa reflected the shortcomings of public schools in English education, but eikaiwa schools never genuinely challenged the Japanese educational system. The eikaiwa model responded to a flaw in the system by propping up the broken system with a niche supplement intended to compensate for the public-school deficiencies.

In doing so, eikaiwa schools were effectively as broken as public schools. Teaching conversation divorced from the rest of English is as backwards as teaching grammar-translation. The growth of eikaiwa schools in Japan was a reaction to the weaknesses of public-school teaching, but eikaiwa schools, by the very label “eikaiwa,” were largely stuck in the same mentality that grammar and speaking are somehow separate.

Even as Japanese education attempted to reincorporate communication into English instruction, the system has largely maintained this division between “eigo” (English language) and “eikaiwa” (English conversation). This can be seen at most high schools, where students receive an “English Communication” course separate from their main English course. What nonsense! All English is communication!

Ending the eikaiwa mindset

I am not a conversation teacher. I teach conversation. I also teach grammar, vocabulary, phonics, reading, writing, questioning, inference, summary, reflection, logic, and a host of other language-related, culture-related, communication-related skills. Language learning progresses faster when reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills are taught in an integrated approach. Separating out “conversation” as a primary or exclusive focus for a once-a-week lesson is not highly productive. Nonetheless, eikaiwa remains a feature of many adult-level lessons in Japan, particularly in the online conversation market. Most language schools traditionally labeled “eikaiwa, especially those focused on children, have typically grown past the “conversation” label to teach English with a more rounded approach.

Some language schools in Japan remain heavily focused on “fun” and “conversation.” They remain locked in the outmoded and unhelpful eikaiwa mindset. Yes, fun is necessary. Yes, conversation is necessary. These two pillars alone are not sufficient for a robust learning environment. MY’s purpose is to grow success, which we achieve best through meaningful communication in English. Meaningful communication requires far more than just “conversation.” Engaging students in English requires more than just “fun.” MY English School is not an “eikaiwa.” MY is a language school.

The “eikaiwa” label is inaccurate to what I do and reinforces Japanese cultural ideas about English that are harmful to language learning. This is why I object to “eikaiwa.” As Japan continues to develop better mindsets about English language and education, “eikaiwa” is a label that is better left behind in history.

There are still some “eikaiwa” schools in Japan, but MY English School isn’t one of them. I wouldn’t teach at MY if it were. I’m a language teacher. I don’t teach conversational students. I teach language students. I teach at a language school.