Why do we teach phonics?

Because it works.

Earlier this month, I attended David Paul’s one-day “Teaching English to Children” course in Tokyo. (David authored the Finding Out series that MY English School uses in our elementary-age classes. We have him scheduled to present at MY this year in October.) I attended David’s seminar previously in Sendai about six years ago. Attending a second time after several years was a good experience. Sometimes we need a refresher in the basics.

One point that David stresses in his seminar is that we should teach reading using phonics because phonics works. Phonics is proven. It’s tested. Phonics gets results. It gets better results than any other system. Kids of all backgrounds learn to read best when they start with well-taught phonics.

In the couple weeks following David’s seminar, two news items popped to my attention underscoring the point that phonics works:

Mississippi

The first is a news article dated from last month about the Gulf States of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama. This article offers a lot of hope: Mississippi raised its 4th grade reading level from second-to-last in 2013 to 21st in the nation in 2022. How did Mississippi accomplish this? By emphasizing phonics.

For those unfamiliar with education in the United States, education is determined and administered at the state level. Federal funding sometimes coerces states into following certain national standards, but states are generally able to set their own curricular and teaching standards.

For decades, Mississippi’s educational system has been the butt of jokes. When I was a student in my home state of Idaho, Idaho’s educational achievement was middle-of-the-road, but our educational spending per student was 49th in the nation. The one state below us? Mississippi. “At least we’re not Mississippi” and “Thank God for Mississippi” were common refrains.

No longer!

Leaping 28 places in state rankings in less than a decade makes it hard to joke about Mississippi anymore. Using a similar approach, Louisiana and Alabama have made similar gains and were two of only three states to see gains in 4th-grade reading skills during the three years of the pandemic. Other states are taking notice of that success. Phonics works.

NCTQ

The second item is a mix of good news and bad news. The National Council on Teacher Quality this month released its findings on elementary reading instruction in the United States.

The bad news? There is plenty:

- Only 60 percent of American kids are literate by 4th grade.

- 72 percent of teachers report using teaching methods for reading that have been debunked by science.

- Only 25 percent of university teacher preparation programs adequately address five core components of reading instruction.

- 71 percent of teacher preparation programs give less than two hours of instruction about teaching reading to English language learners.

- 88 percent of programs provide no practice in teaching reading to English langauge learners.

- 58 percent of teacher preparation programs devote less than two hours of instruction to supporting struggling readers.

- 81 percent of programs provide no practice opportunities on teaching struggling readers.

In short, America is not effectively training teachers how to teach reading, and too many kids are not learning how to read.

The good news? With emphasis on the science of reading (with phonics as a core element), the United States could raise that 60 percent literacy rate to 90 percent within a few years.

Phonics is making gains. Mississippi set itself on a firm path a decade ago. Other states are doing the same and getting similar positive results. It’s simply a matter of will. Will states, schools, and teachers choose to teach using the proven method?

Sadly, there remains considerable resistance to phonics in American universities and among some educators. The misguided “Reading Wars” have left a terrible legacy in the United States. Teachers too often don’t know how to teach reading. Kids too often don’t learn how to read.

The Science of Reading

Academic and scientific fields have given themselves many black eyes in recent decades. The “whole-language” approach to reading is one example of this from education. Across many fields, however, science is flailing. “Science” as a term is frequently bandied in almost cult-like ways, aimed at discrediting anyone who disagrees. However, when 60 to 80 percent of published, peer-reviewed research is irreproducible, it throws up a question what it means to “follow the science.” People posturing rhetorically that they “follow the science” or “stand behind the science” are too often misrepresenting the science that they claim to stand behind. Consequently, trust in science and expertise is declining.

For me, the label “the science of” anything raises my suspicions. Is this posturing? Or is there real knowledge here to learn? When I hear “science of reading,” alarm bells ring. Given the mess created by whole language and balanced literacy approaches in the 1980s and 1990s, skepticism toward experts about reading is justified.

This said, reading has a science behind it. On the practical side, we have decades of experimentation in the classroom. On the neuroscience side, recent brain research has helped us understand the brain mechanics of reading. Reading and the teaching of reading are heavily researched, with clear answers about the best approach and practices for teachers and students. The NCTQ’s report neatly summarizes the five components of the science of reading:

- Phonemic awareness: The ability to focus on and manipulate the individual phonemes in spoken words.

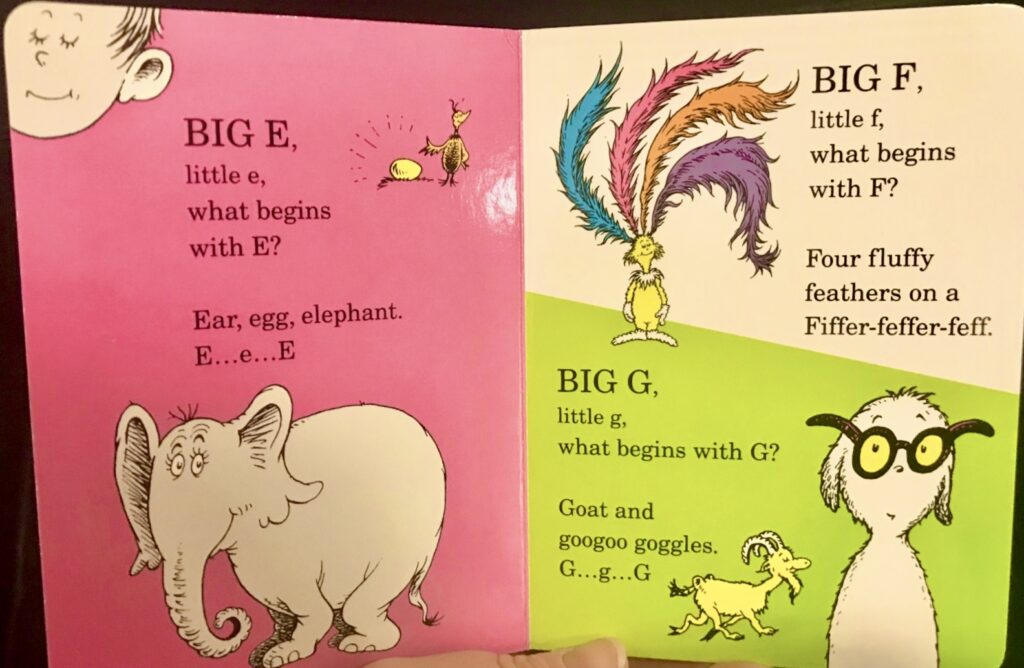

Why are children’s storybooks full of funny-sounding nonsense words? These are often books meant to be read by parents to children (not decoded by children themselves). Dr. Seuss’s ABC remains deeply burned in my mind:

Big G, little g, what begins with G?

Goat and googoo goggles, G…g…G!

What are googoo goggles? Aren’t they just glasses? Why not use “glasses”? And the letter before that? What the deuce is a Fiffer-feffer-feff? Repetitive phonemes twist into words to produce utter nonsense.

The point is to build phonemic awareness. “Googoo goggles” plays with the phonemes, encouraging pre-literate children to do the same.

Likewise, why are rhymes important to young children? Because kids learn to match sounds and change words by manipulating individual phonemes. Children may not be able to decode the letters written on the page yet, but the ability to play with sounds displays phonemic awareness.

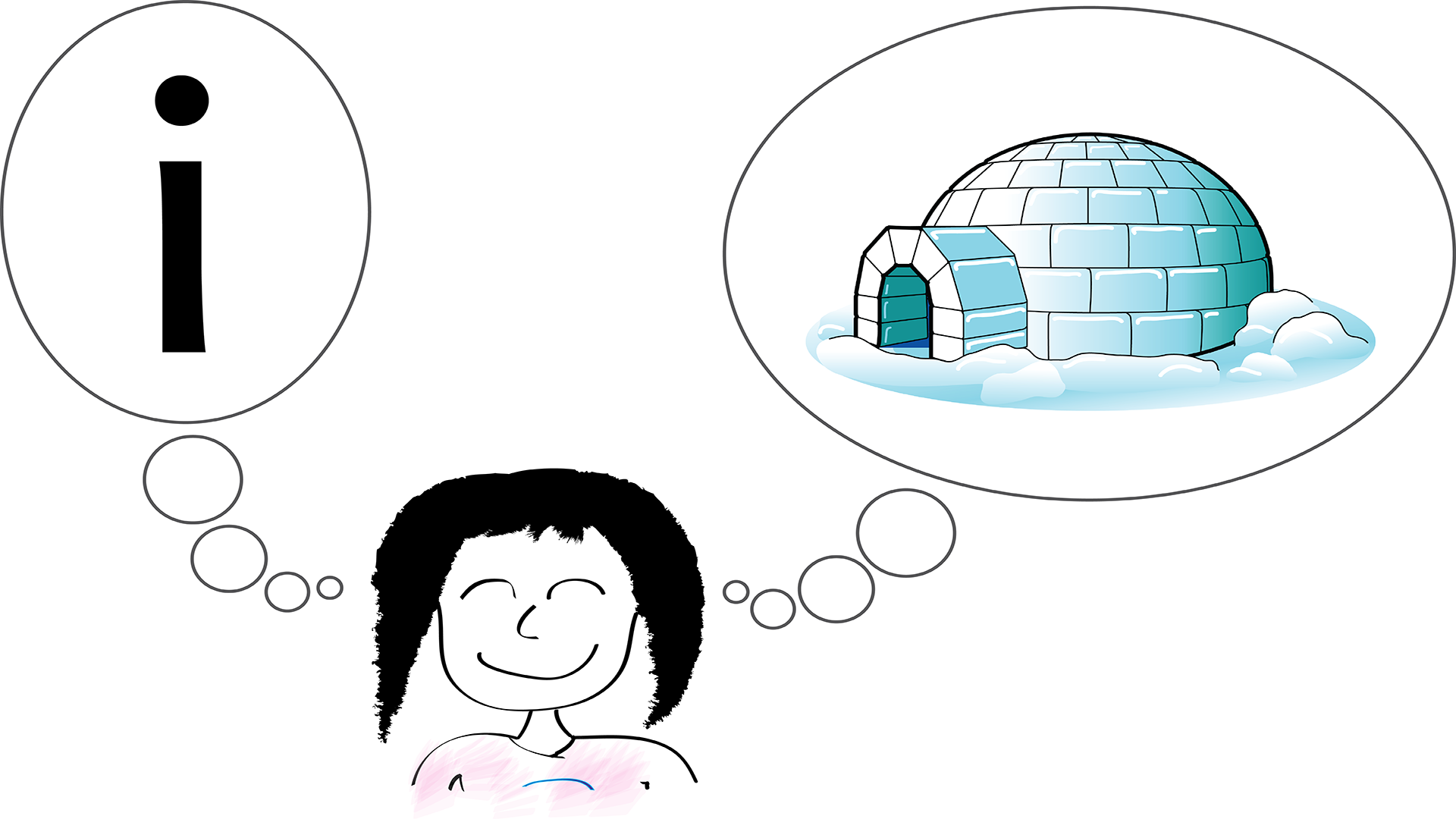

- Phonics: The relationship between the sound of spoken words and the individual letters or groups of letters representing those sounds in written words.

Phonics is the first stage of literacy, where written letters and words begin to form and match with spoken language. Phonics is not the end of reading. It is a tool for reading and a middle stage of reading. Decoding words using phonics offers nascent readers the best opportunity for matching what is written with the spoken vocabulary that they already know, in hope of then comprehending meaning. Phonics allows them to approximate pronunciation, opening the door to asking questions about vocabulary that they don’t know. Various context cueing, guessing, and other whole-language techniques simply fail to provide students the accuracy and speed of phonics decoding.

- Fluency: The ability to read a text accurately and quickly while using phrasing and emphasis to make what is read sound like the spoken language.

Teachers and students often refer to fluency imprecisely with respect to reading. What people often mean by “fluency” is closer to comprehension or sometimes speed. It is remarkable how little attention fluency can receive in reading lessons.

I am often guilty of this. I have spent dozens of hours helping an individual student produce clear phrasing and emphasis of a written text for a speech competition. In regular lessons, however, do my students read like fast-paced robots? Too often, yes.

Written language is meant to capture the rhythm, flow, and expression of spoken language. If students don’t read with the correct phrasing and emphasis, they are not learning to read well.

Reading fluency deserves more attention in teaching.

- Vocabulary: Knowledge about the meanings, uses, and pronunciation of words.

Reading is not a single skill or a collection of purely skills. Skills like decoding and phrasing are important components of reading. However, reading also requires content knowledge. This means learning vocabulary.

- Comprehension: Constructing meaning that is reasonable and accurate by connecting what has been read to what the reader already knows.

Comprehension is our ultimate aim when reading. To comprehend, a reader needs the previous four components of reading, plus adequate understandings of grammar and context, plus the ability to reflect upon all this and connect it to the reader’s existing schema. Whew…that’s a lot wrapped up in one component.

What does this mean for EFL teaching?

I teach in Japan. The above reports are from America. Teaching in America is to native speakers or in an ESL environment. Teaching in Japan is in an EFL environment. Does the teaching context make a difference for reading and phonics?

Yes and no.

EFL is a different context for learning reading, especially in a country like Japan that does not share the same alphabet with English and where children typically get little English exposure outside lessons. In this respect, teaching phonics is even more critical.

Japanese children start with a different schema from native English speakers. Their existing phonemic awareness is of Japanese kana phonemes. English phonemes are not going to map well onto their existing schema. How are Japanese children supposed to play with sounds that they do not yet know? Teaching phonemic awareness, phonics, reading fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension in this EFL context forces teachers to adapt from how teachers of native-English students teach. Regardless, the NCTQ’s five elements for reading programs still apply:

- Japanese children need activities to develop English phonemic awareness.

- They need phonics in order to match sounds to written letters and develop strong decoding skills quickly.

- They need the accurate rhythm, emphasis, and phrasing that come with fluency.

- Their vocabulary needs to grow steadily in breadth and depth.

- Japanese children need the comprehension skills to make sense of texts and connect what they read to what they already know.

How we employ teaching techniques in EFL to achieve these goals may change. The target components of good reading instruction remain firm.

In my experience, sadly, most public education in Japan skips past phonemic awareness and phonics, or gives them cursory attention at most. Fluency instruction is similarly more miss than hit. The overbearing focus remains on vocabulary, grammar rules, and narrow comprehension of the current text in isolation. These shortcomings in public education offer opportunities for private language schools. Phonics and good reading instruction help students grow.

How does your school’s teacher training and reading time match with the NCTQ criteria for science-based reading instruction?

How about the TEFL certificates that teachers at your school have taken? Do those TEFL certificate programs teach science-based reading?

How do your students learn phonemic awareness? How well are they using phonics to bridge between sounds and written letters? What are you doing with students to develop their reading fluency? If you teach at a private language school in Japan, there is already heavy emphasis on vocabulary in public school–how do you deal with vocabulary? Are your students adept at comprehending passages to the level that they connect new ideas with what they already know?

These are a lot of questions to reflect on, which provide lots of opportunities to grow as schools and as teachers.